The Power of Akka Streams

April 25, 2020In the previous article: Parallel processing with Scala and Akka Actors I have explained how to design actor-based applications. The example I presented is too simple, and using actors to solve that is obliviously overkilling. Still, I think it is representative enough to show everything necessary to get started with building actor-based applications.

Actors are the core of Akka toolkit, and they can’t be replaced, but actors back every module in the Akka toolkit. The purpose of these modules is to help engineers abstract over low-level actor-based code and focus on business logic. The result of using these modules is boilerplate-free code, which is also less error-prone. In this article, the same example will be used to show how Akka Actors can be replaced with a few lines of Akka Streams code. Check all modules provided by Akka.

The tasks like moving and transferring data can be implemented with actors. Still, it demands a lot of code to implement necessary mechanisms for stream processing workloads like back-pressure, buffering, and transforming data or error-recovery. So, for designing stream processing topologies with built-in back-pressure, Akka Streams should be considered.

Basic terminology

- Source is a component that emits elements asynchronously downstream. It’s a starting point of every streaming topology any only has output.

A source can be created from any Scala collection, and it can be a Kafka topic, or it can be made from constantly polling some HTTP endpoint, etc. Here’s a simple source created from Scala List that contains hashtags.

val source = Source(List("#Scala", "#akka", "#JVM", "#Kafka"))- Sink is a component that receives elements, and as the opposite of the Source, it’s usually the final stage of a stream processing topology. It only has input.

A sink can be a Scala collection, Kafka Topic, or even an Akka Actor. Here is a list of all possible sinks. Example of creating a simple sink, which will print every element it receives.

val sink = Sink.foreach[String](element => println(element))Note that the type parameter of the receiving element must be provided.

- Flow is a component that has both input and output. It’s basically a component that receives the data, transforms it, and passes it downstream to the sink or to the next flow in topology. Example of a few flows:

val removeHash = Flow[String].map(element => element.substring(1))

val toLowerCase = Flow[String].map(element => element.toLowerCase)

val filter = Flow[String].filter(element => element.length > 3)Same as creating a sink, we must provide a type parameter for the input element of the flow. These flows are pretty self-explanatory and straightforward. The first flow removes the hash from the input element, the second transforms string to lowercase, and the third filters strings based on their length.

So you must be asking now how to connect all these separate components to create stream processing topology. Pipelining all components we defined earlier, we will create a graph, or how Akka it calls RunnableGraph. We know that source is a starting point, the sink is the last, and flows are somewhere in the middle. Our graph represents just a description of topology. It is completely lazy.

val graph = source.via(removeHash).via(toLowerCase).via(filter).to(sink)Data will start to flow through it only after we run the graph. Running a graph will allocate the needed resources to execute topology, like actors, threads, etc.

Running a graph is as simple as invoking a run method on it.

graph.run()If you try to execute the code we have written so far, it will not be possible. We need to create ActorMaterializer since the run method implicitly accepts it to execute a stream. Upon creation ActorMaterializer requires an ActorSystem. So every Akka Stream application starts with these two lines:

implicit val system = ActorSystem("actor-system")

implicit val materializer = ActorMaterializer()Since Akka 2.6 version, there is no need for ActorMaterilzer because a default materializer is now provided out of the box if implicit ActorSystem is available.

Akka Streams API provides a builder pattern syntax to chain source, flow, and sink components to create a graph. IMHO it’s better to use it than creating separate components and then connecting them. Our stream processing app can be rewritten to look like this:

object Main extends App {

implicit val system = ActorSystem("actor-system")

Source(List("#Scala", "#akka", "#JVM", "#StReam", "#Kafka"))

.map(element => element.substring(1))

.map(element => element.toLowerCase)

.filter(element => element.length > 3)

.to(Sink.foreach(element => println(element)))

.run()

}A few more tricks can be applied to implement this in an even better way.

Source(List("#Scala", "#akka", "#JVM", "#StReam", "#Kafka"))

.map(_.substring(1))

.map(_.toLowerCase)

.filter(_.length > 3)

.runForeach(println)Back-Pressure in a Nutshell

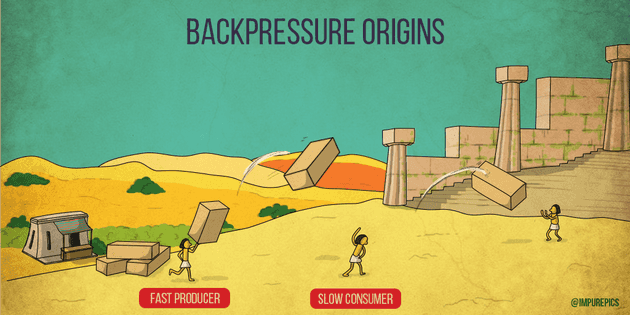

To explain what back-pressure let’s consider the following two cases:

- Slow source/publisher, fast sink/consumer is ideal because the publisher doesn’t need to slow down message emitting. Since the throughput of stream elements isn’t constant and the publisher can start emitting elements faster, back-pressure still should be enabled.

Image by: impurepics

Image by: impurepics

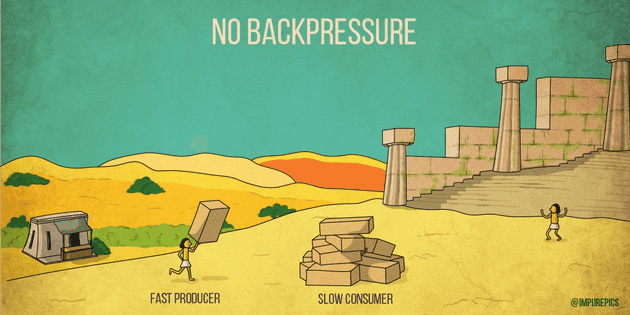

- Fast source/publisher, slow sink/consumer is a case where we need a back-pressure mechanism since the consumer cannot deal with the rate of messages sent from the producer.

Image by: impurepics

Image by: impurepics

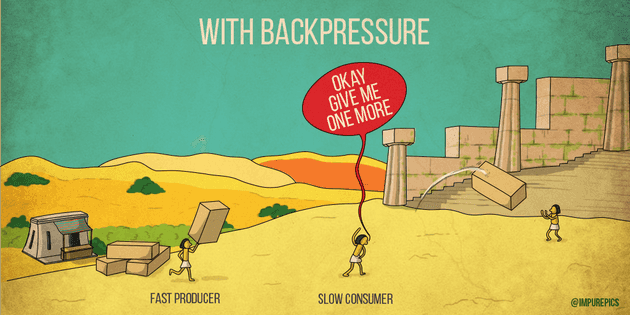

So the back-pressure is a mechanism where downstream components inform upstream components about the number of messages that can be received and buffered.

Akka Streams already has a back-pressure mechanism implemented. The library user doesn’t have to write any explicit back-pressure handling code since it’s built-in into Akka Streams operators. Anyhow, Akka provides the buffer method with overflow strategies if you need it.

Image by: impurepics

Image by: impurepics

Real Example

Now when we are equipped with the powerful tools we examined earlier, let’s refactor data processing application from Parallel processing with Scala and Akka Actors article that uses Akka Actors and replace them with Akka Streams.

As I mentioned several times Source is an entry point for every topology. So firstly, we are going to create a source from the file path. Akka gives us the FileIO component, a container of factory methods to create sinks and sources from files. Let’s review fromPath method signature.

def fromPath(f: Path, chunkSize: Int = 8192): Source[ByteString, Future[IOResult]]The path parameter is mandatory, while the chunkSize default value is provided, representing the size of each read operation. Since I didn’t explain Source in detail, let’s do that now. Source has two type parameters, and the first one represents a type of element which will be emitted downstream. In this particular case, it is a ByteString, Akka utility class, an immutable data structure that provides a thread-safe way of working with bytes. When reading or writing to files, Akka always uses this type. The second type parameter is the materialized value of the source. Materialized value is obtained when the runnable graph is executed. Since Akka Streams are asynchronous by default, it will return Future of IOResult. Scala Future represents a value available at some point or an exception if that value can’t be computed. A Future starts execution immediately when you create it and returns a result at some point. To start, a Future implicit ExecutionContext must be available since Future is potentially executed on a different thread.

Since fromPath method reads byte chunks, and our weblog.csv should be read line by line we need to use one more Akka Streams utility method from Framing module. Implementation of line delimiter flow goes like this:

val lineDelimiter: Flow[ByteString, ByteString, NotUsed] =

Framing.delimiter(

ByteString("\n"),

maximumFrameLength = 256,

allowTruncation = true

)To read more about this flow read offical documentation. The method is pretty simple and commonly used, so I hope you understand that in full.

val path = Paths.get(getClass.getClassLoader.getResource("data/weblog.csv").getPath)

val source: Source[ByteString, Future[IOResult]] = FileIO

.fromPath(createPath)

.via(lineDelimiter)Finally, we implemented a source that will read a file line by line, but it will emit ByteString, and we need String. Luckily, ByteString has a method that decodes it to UTF-8 encoded String. So we need to attach some flow that will perform that decoding. Of course, it is gonna be Flow[ByteString].map(…).

val source: Source[String, Future[IOResult]] = FileIO

.fromPath(createPath)

.via(lineDelimiter)

.map(byteString => byteString.utf8String) // or .map(_.utf8String)When a source is modified to emit lines, we are ready to implement our processing logic, which you are already familiar with. Keep every line that starts with a valid IP address, extracts status code from it, and counts the number of occurrences of status code in a given file.

val path = Paths.get(getClass.getClassLoader.getResource("data/weblog.csv").getPath)

def validateIp(line: String): Boolean = {

val ipRegex = """.*?(\d{1,3})\.(\d{1,3})\.(\d{1,3})\.(\d{1,3}).*""".r

ipRegex.matches(line.split(",")(0))

}

def extractStatusCode(line: String): String =

line.split(",").toList match {

case _ :: _ :: _ :: status :: _ => status.trim

}

FileIO

.fromPath(createPath)

.via(lineDelimiter)

.map(byteString => byteString.utf8String) // or .map(_.utf8String)

.filter(line => validateIp(line)) // or .filter(validate)

.map(line => extractStatusCode(line)) // or .map(extractStatusCode)I hope you are already familiar with these helper methods since they are already implemented in the actor’s version of this application.

Now things can get a little bit complicated, but with a great Akka Streams DSL, it will look quite simple. To count occurrences of each status code in a stream, we should branch it into sub-streams based on a key, in this case, its incoming status code. Akka Streams have a groupBy operator that accepts a maximum number of substreams and a function used to compute key for a given record. In our case, the maximum number of substreams will be five since we have five distinct status codes (we know this based on the results of actor-based application). If we set the number of maximum substreams to be more than five, the results will be the same. The output of groupBy will be five distinct streams since we have five unique values of status codes. Example of using groupBy:

groupBy(5, identity)Since we are partitioning stream by status code, and status code is already an element of the stream, we will use the identity function that returns its input value.

After groupBy, we will have five substreams. To calculate the number of occurrences, we need to transform incoming status codes into key-value pairs, where the key will be a status code, and the value will be one since it’s the first appearance of that key in a stream so far. If you are familiar with Apache Spark, you know that the reduceByKey operator can do the job for us if we were using PairRDD. Unfortunately, Akka Streams doesn’t have that operator. Still, it can be easily implemented with the reduce operator, which accepts the current and subsequent value of a sub-stream yielding the next current value. After applying the reduce operator, we should merge all sub-streams into one stream and pass it to the sink. In our case, the sink will be the Scala collection of tuples, where the first element of the tuple is the status code, and the second one is the count of occurrences.

val processorResult: Future[Seq[(String, Long)]] = FileIO

.fromPath(createPath)

.via(lineDelimiter)

.map(byteString => byteString.utf8String) // or .map(_.utf8String)

.filter(line => validateIp(line)) // or .filter(validate)

.map(line => extractStatusCode(line)) // or .map(extractStatusCode)

.groupBy(5, identity)

.map(statusCode => statusCode -> 1L) // or .map(_ -> 1L)

.reduce((left, right) => (left._1, left._2 + right._2))

.mergeSubstreams

.runWith(Sink.seq[(String, Long)])Here is our completed stream processing topology with all connected components. A Runnable Graph is executed asynchronously, so a result of our processing is Future that contains a collection of tuples.

If Future is completed successfully, we will sort our results, print them to the console, and terminate our ActorsSystem. We learned that it was the best practice when Akka finished its job. Otherwise, we will terminate our ActorsSystem, terminate the currently running JVM, and exit the program with status code 1, which indicates that something went wrong.

processorResult.onComplete {

case Success(result) =>

result.sortBy(_._2).foreach(println)

system.terminate()

case Failure(_) =>

System.exit(1)

}Improving Throughput

Suppose you read Parallel processing with Scala and Akka Actors. In that case, you know that we parallelized our processing workflow, spawning multiple worker actors, and in a round-robin fashion, distributed tasks to them. The goal of this chapter is to show you how to parallelize Akka Streams workflows. Just to let you know that in our case, it won’t have any significant impact. It probably will be slower since our data is small, and spawning multiple actors will be overhead. But in the real world, it’s essential to understand and apply techniques that will be presented.

There are a few techniques for improving Akka Streams performance. We will talk about Operator Fusion, Asynchronous Boundaries, mapAsync / mapAsyncUnordered, and Buffering.

When someone says that stream components/operators are fused, each stage of processing topology will be executed within the same Actor. Akka will fuse the stream components/operators by default. That’s the definition of Operator Fusion. The benefits of this are avoiding the overhead of asynchronous message passing across multiple actors, and fused components allocate only one CPU core.

asynchronous boundaries must be inserted manually between operators using the async method to enable parallel execution of stream operators **.

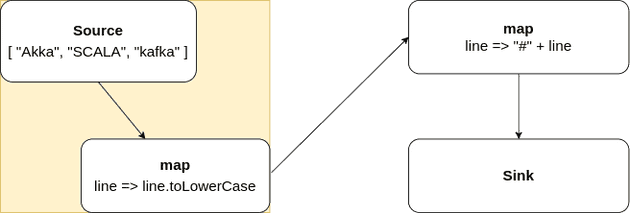

Source(List("Akka", "SCALA", "kafka"))

.map(_.toLowerCase)

.async

.map(line => s"#$line")

.runForeach(println)In this simple example, there’s a source of strings that we want to transform into hashtags. The asynchronous boundary is inserted between map operators, which means that the first two operators, Source and map, will be executed on one actor, and other map and Sink on another one. Communication between the first two operators and the last two will be done via the standard actor’s message passing.

In this diagram, operators inside the yellow box will be executed on one actor, but every other operator outside the box will be performed on another actor. I hope that these two examples were enough to understand what an asynchronous boundary is.

Another way to introduce parallel processing into Akka Streams is to use methods mapAsync and mapAsyncUnordered.

The first argument of the mapAsyc method is the number of Futures that shall run in parallel to compute the result. Another argument is a function that accepts element and returns a Future of a processing result. When Future is completed, the result is passed downstream. Regardless of their completion time, the incoming order of elements will be kept when results are complete. When the order is not essential, mapAsycUnordered should be used because as soon as Future is completed, results will be emitted downstream. This will improve performance.

Both mapAsync and mapAsyncUnordered method signatures are the same.

def mapAsync[T](parallelism: Int)(f: Out => Future[T]): Repr[T]

def mapAsyncUnordered[T](parallelism: Int)(f: Out => Future[T]): Repr[T]The last trick we are going to talk about is buffering. It’s simplest of all we described before. To introduce buffering capabilities into your processing topology, insert the buffer method between Akka Streams operators.

def buffer(size: Int, overflowStrategy: OverflowStrategy): Repr[Out]This method accepts the maximum number of elements that should be buffered and an OverflowStrategy. Akka Streams provide a few overflow strategies. To read more about them, check the official documentation.

Refactoring

So far, a lot of Akka Streams capabilities are exposed. In this chapter, the initial example will be refactored following some of the best practices.

object Application extends App with LazyLogging {

implicit val system = ActorSystem("actor-system")

implicit val dispatcher = system.dispatcher

val processor = new LogProcessor("data/weblog.csv")

val processorResult: Future[Seq[(String, Long)]] = processor.result

processorResult.onComplete {

case Success(result) =>

logger.info("Stream completed successfully.")

result.sortBy(_._2).foreach(println)

system.terminate()

case Failure(ex) =>

logger.error("Stream completion failed.", ex)

system.terminate()

System.exit(1)

}

}Here is the application entry point with defined ActorSystem and dispatcher, an ExecutionContext needed to run Futures. I’m using a dispatcher from the actor system in this example, but the best practice is to introduce a separate one for Future execution.

In the LogProcessor class, all stream processing logic is contained. It accepts file path and implicitly requires an ActorSystem and ExecutionContext.

class LogProcessor(path: String)(implicit system: ActorSystem, ec: ExecutionContext) {

def result: Future[Seq[(String, Long)]] =

FileIO

.fromPath(createPath)

.via(lineDelimiter)

.mapAsyncUnordered(2)(data => Future(data.utf8String))

.async

.filter(validateIp)

.mapAsyncUnordered(2)(line => extractStatusCode(line))

.buffer(1000, OverflowStrategy.backpressure)

.groupBy(5, identity)

.mapAsyncUnordered(2)(status => Future(status -> 1L))

.reduce((left, right) => (left._1, left._2 + right._2))

.mergeSubstreams

.runWith(Sink.seq[(String, Long)])

private val createPath: Path =

Paths.get(getClass.getClassLoader.getResource(path).getPath)

private val lineDelimiter: Flow[ByteString, ByteString, NotUsed] =

Framing.delimiter(

ByteString("\n"),

maximumFrameLength = 256,

allowTruncation = true

)

private def validateIp(line: String): Boolean = {

val ipRegex = """.*?(\d{1,3})\.(\d{1,3})\.(\d{1,3})\.(\d{1,3}).*""".r

ipRegex.matches(line.split(",")(0))

}

private def extractStatusCode(line: String): Future[String] = Future {

line.split(",").toList match {

case _ :: _ :: _ :: status :: _ => status.trim

}

}

}In the result method, I showed how to introduce asynchronous boundaries and enable parallel processing of stream elements. Probably this is not optimal topology, but I introduced them for learning purposes. It would be best to be careful when using these techniques in stream processing because there are no rules on how to use them. Different topologies should be designed and benchmarked to increase performances since I already mentioned that async boundaries introduce the overhead of asynchronous message passing. Still, there are cases where this could significantly improve the overall performance of a streaming workflow.

Summary

In this article, many Akka Streams capabilities are explained with a few examples, but it’s is just the tip of the iceberg. There is the Akka Streams Graph DSL, which helps us to build non-linear and quite complex stream processing topologies. Also, I did not talk about error handling and recovery, and both of these may be the subject of the following articles.

If you are interested in source code, here is the Github repository that complements examples from this article.

You can find me at:

Or send me a question to skrbic.alexa@gmail.com